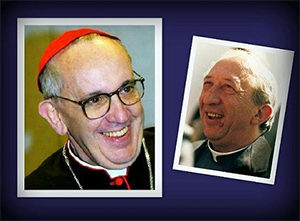

Bergoglio and Giussani

The underlying harmony between the future Pope and the future Blessed (God willing): from man as “religious” to the Christian “encounter.”

Posted by Alver Metalli in Chiesa, In evidenza, Società Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio never met Mons. Luigi Giussani in person; nevertheless, it is undeniable that, on the ideal plane, an encounter took place. On four occasions, Bergoglio presented Spanish editions of Giussani’s books in Buenos Aires: in 1999, El sentido religioso; in 2001, El atractivo Jesucristo; in 2005, ¿Por qué la Iglesia?; in 2008, Se puede vivir así? As he confessed in 2001, there were two reasons that brought him into consonance with Giussani. “The first, more personal, is the good that this man has done for me, for my life as a priest, in the last 10 years, through my reading of his books and articles. The second reason is that I am convinced that his thought is profoundly human, and reaches even the most intimate part of human yearning. I would dare say that it is the most profound, and, at the same time, most comprehensible phenomenology of nostalgia as a transcendental fact.” Bergoglio was referring to the anthropological vision clarified in The Religious Sense, a text by Giussani that he had presented in 1999. “For many years,” he affirmed on that occasion, “Monsignor Giussani’s writings have inspired my reflection […]. The Religious Sense is not a book for the exclusive use of those who are part of the Movement, nor is it only for Christians or believers. It is a book for all men who take their own humanity seriously. I dare say that, today, the question that we must primarily face is not so much the problem of God–the existence of God, the knowledge of God–but the problem of man, the knowledge of man, and finding in man himself the imprint that God left there, in order to meet him. […] If a man has forgotten or censored his fundamental ‘whys’ and the longing of his heart, the fact of speaking to him about God proves to be an abstract, esoteric discourse, or a push toward a devotion with no bearing on life. One cannot begin a discourse about God without first blowing away the ashes that suffocate the burning embers of the fundamental ‘whys.’ The first step is to create the sense of those questions that are hidden, buried, perhaps suffering, but that exist.” Here, Bergoglio’s reading coincides, to the letter, with what Giussani writes: “The religious factor represents the nature of our ‘I’ in as much as it expresses itself in certain questions: ‘What is the ultimate meaning of existence?’ or ‘Why is there pain and death, and why, in the end, is life worth living?’” For the then-Cardinal of Buenos Aires, having come from the Jesuit school, this transcendental nostalgia undoubtedly reminded him of the transcendental anthropology developed by Karl Rahner. The points of agreement between Giussani and Rahner did not, however, erase the differences. Giussani had developed and articulated his notion of the “religious sense” in 1958, following the particular Thomistic formulation given by the Cardinal of Milan, Giovanni Battista Montini, in his 1957 Pastoral Letter, On the Religious Sense. In this letter, the religious dimension was explained as vis appetitiva–as need for truth, not criterion of truth–thus avoiding the a priori risk that underlies the Rahnerian formulation, strongly dependent on Kantian transcendentalism. This explains the significance that the category of encounter assumes in Giussani. The encounter is the modality with which the Mystery reaches man through the senses, touches him in space and time with signs that provoke him to a response. The encounter is the concrete modality through which the religious sense passes from potency to action, goes from being latent to manifest. The transcendental formulation, the innate need for God entered a priori into our nature, does not thus eliminate the novelty of the a posteriori, the unpredictable modality with which the action of God–grace–manifests itself. For this reason, Bergoglio, still commenting on the Giussanian notion of religious sense, affirms: “On the other hand, in order to interrogate ourselves when faced with signs, an extremely human capacity is necessary, the first one that we have as men and women: wonder, the capacity to be amazed, as Giussani calls it, ultimately the heart of a child. Only wonder knows. […] The cultural opiate tends to obliterate, weaken, or kill this capacity for wonder. The beginning of any philosophy is wonder. There is a phrase of John Paul I that says that the drama of contemporary Christianity lies in the fact of putting categories and norms in the place of wonder. Wonder comes before all categories. It is what brings me to search, to open myself; it is what makes my response possible, and it is neither a verbal nor a conceptual response. Because if wonder opens me as a question, the only response is the encounter–and only in the encounter is thirst quenched.”

Religious anthropology, on the one hand, and the encounter as modality with which faith happens, on the other, are the two poles that, for Giussani as well as for Bergoglio, indicate the point of the Christian question today. Christianity does not manifest itself as a series of precepts or values. “Being a Christian,” writes Francis in Evangelii Gaudium, citing Benedict XVI, “is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (7). Analogously, in the presentation of Giussani’s text L’attrattiva Gesù (The Attraction of Jesus), he affirmed: “Everything in our life, today as in the time of Jesus, begins with an encounter–an encounter with this man, the carpenter from Nazareth, a man like all the others, and, at the same time, different. The first ones–John, Andrew, Simon–discovered that they were looked at in their very depths, read deep down, and a surprise was generated in them, a wonder that, immediately, made them feel tied to Him, that made them feel different. […] One cannot understand this dynamic of the encounter that arouses wonder and adhesion without the “trigger” of mercy. Only those who have encountered mercy, who have been caressed by the tenderness of mercy, get on well with the Lord. […] The privileged place of the encounter is the caress of the mercy of Jesus Christ toward my sin.” A series of very important consequences derives from this point, on which there is total accord between Bergoglio and Giussani.

The first is that grace precedes, comes before. In the presentation of L’attrattiva Gesù, Bergoglio affirms that “The encounter happens […]. This is pure grace. Pure grace. In history, from when it began up until today, grace always primerea–comes first–and then comes all the rest.” In his book, Giussani had referred to an article of his that appeared in 30Giorni (4, 1993), entitled Qualcosa che viene prima (Something That Comes Before). In L’attrattiva Gesù, “the ‘something that comes before’ is the encounter with Christ, even if unclear, not truly aware–as, for John and Andrew, it was something astonishing, not definable by them. The thing that comes first, grace, is the relationship with Christ: Christ is the grace, it is this Presence, and it is your relationship with it, your dialogue with it, your way of looking at it, thinking about it, focusing on it” (p. 24).

The second consequence is that, if the encounter is the essential modality with which faith is communicated, yesterday and today, then, in a world that has returned, to a large extent, to being pagan, Christianity will have to manifest itself in its essential form and not, primarily, in its ethical consequences, whose defense, in the public arena, is up to lay Christians involved in temporal affairs. In the methodological text Riflessioni sopra un’esperienza (Reflections on an Experience, 1959), Giussani had already proposed a Christian exhortation that was “simple and essential,” since “the Church is very discrete in fixing the obligatory points.” He later wrote, in Uomini senza patria (Men Without a Homeland, 1982), that “As long as Christianity is dialectically and practically sustaining Christian values, it will find plenty of room and a welcome everywhere.” Pope Francis, on his part, said in his interview with Fr. Antonio Spadaro, “The dogmatic and moral teachings of the Church are not all equivalent. The Church’s pastoral ministry cannot be obsessed with the transmission of a disjointed multitude of doctrines to be imposed insistently. Proclamation in a missionary style focuses on the essentials, on the necessary things: this is also what fascinates and attracts more, what makes the heart burn, as it did for the disciples at Emmaus. We have to find a new balance; otherwise even the moral edifice of the Church is likely to fall like a house of cards, losing the freshness and fragrance of the Gospel. The proposal of the Gospel must be more simple, profound, radiant. It is from this proposition that the moral consequences then flow.” The Attraction of Jesus, a term taken up again in Evangelii Gaudium (39), must precede moral doctrine. It precedes it inasmuch as it proceeds from the encounter; it is not possible outside of the encounter. This position impedes the rise of every possible Christian fundamentalism at the origin.

The third and last consequence is the similarity of judgments that unites Bergoglio and Giussani with regard to the risks that contemporary Christianity faces: Gnosticism and Pelagianism. If Christianity is an Event that manifests itself in a historical, perceptible encounter, if this primerea (comes first) with respect to all of our actions or intentions, then the spiritualistic emptying of the Christian fact, the negation of its being flesh, as well as the moralistic presumption of being able to build a new world by oneself, appear as deviations to correct. As Bergoglio wrote in 2001, “this Christianly authentic conception of morality that Giussani presents has nothing to do with the seemingly spiritual quietisms of which the shelves of today’s religious supermarkets are full. And neither does it have to do with the Pelagianism that is so popular in its various and sophisticated manifestations. Pelagianism, at bottom, is a new version of the tower of Babel. Seemingly spiritual quietisms are efforts at prayer or immanent spirituality that never go beyond themselves.” We are dealing, in both cases, with a process of “worldlifying” faith. In Evangelii Gaudium, Francis affirms that “This worldliness can be fuelled in two deeply interrelated ways. One is the attraction of Gnosticism, a purely subjective faith whose only interest is a certain experience or a set of ideas and bits of information which are meant to console and enlighten, but which ultimately keep one imprisoned in his or her own thoughts and feelings. The other is the self-absorbed promethean neo-Pelagianism of those who ultimately trust only in their own powers and feel superior to others because they observe certain rules or remain intransigently faithful to a particular Catholic style from the past. A supposed soundness of doctrine or discipline leads instead to a narcissistic and authoritarian elitism, whereby instead of evangelizing, one analyzes and classifies others, and instead of opening the door to grace, one exhausts his or her energies in inspecting and verifying. In neither case is one really concerned about Jesus Christ or others. These are manifestations of an anthropocentric immanentism. It is impossible to think that a genuine evangelizing thrust could emerge from these adulterated forms of Christianity” (94). It is interesting to note that the present form of neo-Pelagianism is no longer the one that was prevalent in the 1970s–typical of the Christian political theology influenced by Marxism–but a new form, conservative, typical of a certain Catholic traditionalism. In this case, as well, what is essential for the ideal encounter Bergoglio-Giussani is the underlying harmony. Gnosticism and Pelagianism are dangers because Christianity is a real Event that continues in history, and because this Event is the (gratuitous) source of new humanity that cannot be generated by man. What Giussani insistently emphasized in all of his educative witness thus finds in Bergoglio an ideal continuation.